Midnight in Paris (2011) Movie Review

by Rob

(Oxford, United Kingdom)

At his best, Woody Allen has delivered some of the most witty and affectionate portrayals of love, romance and human vulnerability in cinematic history. But, as a director, his phenomenal work rate has also produced some less than convincing efforts too. By the time Midnight in Paris landed in 2011, on the back of a string of underwhelming efforts, Allen was gaining a reputation for inconsistency in his filmmaking. But, with its familiar themes of love, self-analysis and urban culture, Midnight in Paris would appear to tread safe ground for the veteran New Yorker.

As the opening credits roll, the first impression of the movie is the quality of its star-studded cast. Yet, far from the ensemble performance that one might anticipate, it’s Owen Wilson as Gil Pender who does much of the heavy lifting. While other, fine acting talents such as Tom Hiddleston, Kathy Bates and Adrien Brody stroll leisurely in and out of the proceedings; it’s left to Michael Sheen as the charismatic yet pedantic love-rival Paul, and Corey Stoll’s exceptional turn as Ernest Hemingway, to steal scenes time after time.

There’s a common trope among Allen’s work that sees the director placing a version of himself within the film, and it’s Wilson’s Gil who embodies the awkward, insecure misfit archetype this time. In modern day Paris, Gil is a writer making his first foray into serious literature, while simultaneously finalizing plans for his wedding day with fiancée Inez (Rachel McAdams) and her overbearing parents (played flawlessly by Mimi Kennedy and Kurt Fuller).

As Gil grows increasingly apprehensive about his position in life, he finds certainty in his dual loves of Paris and 1920s culture. When he seems to discover a route back to this lost golden age, the film changes gear: opening up into a whimsical tale of magic realism, where Gil inhabits anxiety-riddled 2010 by day and lives a carefree existence with his literary and artistic heroes in the roaring ’20s by night.

It’s a daring premise upon which to construct a film whose central plot points concern the rather conventional worries of true love and finding one’s place in the world. And the high concept approach is not without its problems. The demands placed on the audience to suspend their own disbelief and go along - as Gil does - for the ride puts Midnight in Paris in a precarious position from the outset.

The leaps between past and present can feel, at times, as though they are used to distract the audience from the rather conservative romantic drama that’s lying at the heart of the film. It’s most apparent when meeting the almost endless procession of recognizable cultural icons in the 1920s scenes. Each arrives in turn, delivers a few lines of broadly drawn character dialogue (Hiddleston’s Fitzgerald calls everybody “Sport”; Hemingway is constantly talking about shooting animals or trying to start a fist fight). Once completed, they exit to make way for the next celebrity-cameo as celebrity-cameo in the line. By the time we meet Brody’s Salvador Dali, the sense of magic and wonder has all but dissipated.

But perhaps that’s the point. Because, through Gil, we soon learn that his nostalgia for a long lost past is nothing unique; it is, in fact, a timeless desire whose roots are always found firmly in the present day – whenever that present day might have been. And because of this, Midnight in Paris works. It’s lean, whimsical and consistently witty; with a superb cast that gets the most out of its well-crafted script. It’s a film which accurately displays the human condition – not as something to be judged, but to be enjoyed. And it leaves just a hint of mystery and magic to ensure the audience leaves with a small amount of fondness and nostalgia of their own.

Recent Articles

-

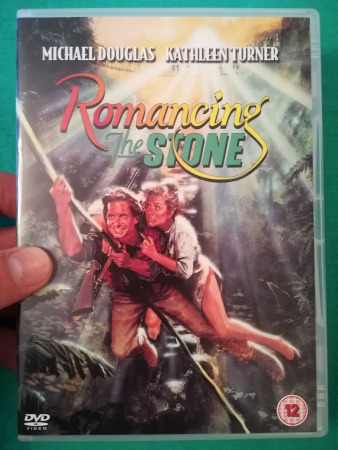

Romancing the Stone (1984) - Rip-Roaring Romance!

Oct 27, 18 05:25 PM

A cracking romantic adventure with terrific characters, Romancing the Stone (1984) may be dated but it’s still good natured and entertaining. -

Alice Movie - Magical Manhattan!

Aug 27, 18 04:13 PM

Stylish and imaginative, Woody Allen’s Alice Movie (1990) is a tale of a privileged New Yorker on the verge of a midlife crisis. -

Working Girl (1988) Movie Review

Aug 02, 18 03:13 PM

Working Girl is a lighthearted movie about an ambitious young woman who wants more out of life than being a secretary and getting married to her loser